The Endowment Effect

Essential Questions

- How do we measure the endowment effect experimentally?

- What mechanisms explain the gap between willingness to pay and willingness to accept?

- How does the endowment effect distort markets for goods, labor, and policy?

Overview

A city plans to convert street parking into bike lanes. Residents asked to give up their spots demand thousands of dollars in compensation, while renters who never had spots would pay little to gain one. This asymmetry stems from the endowment effect: ownership raises perceived value.

In this lesson, you will review classic experiments, use data to calculate WTA-WTP ratios, and explore implications for housing markets, environmental policy, and negotiation strategy.

Measuring the Gap

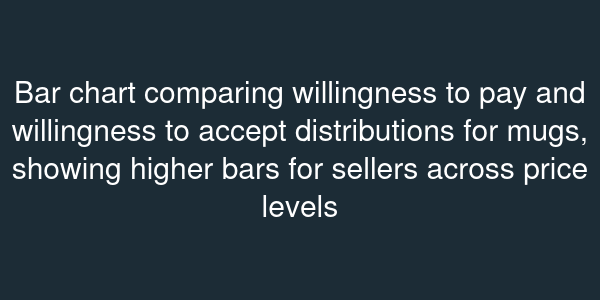

The canonical experiment assigns mugs to half the participants. Sellers state the minimum price they'd accept (WTA), buyers state the maximum they'd pay (WTP). If rational preferences were stable, WTA and WTP should match. Instead, Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler found median WTA around $7 and WTP around $3. You can model the effect by letting the value function depend on an ownership indicator . The utility of quantity becomes where captures attachment. The difference inflates WTA: .

To compute from synthetic data, suppose 40 sellers report WTA values with mean and standard deviation , while 40 buyers report WTP with mean and standard deviation . The average WTA/WTP ratio is . Bootstrapping the difference yields a 95% confidence interval excluding zero, confirming a statistically significant gap.

Mechanisms

Loss aversion is the leading explanation: giving up an endowed item is coded as a loss relative to the reference state of ownership. But other mechanisms contribute. Transaction costs and search friction make sellers demand compensation for hassle. Identity and sentimental attachment create intrinsic value beyond price. Neuroeconomic studies show heightened activity in the insula (linked to pain) when owners consider selling below their valuation.

Market Consequences

In housing, the endowment effect contributes to sticky prices; homeowners resist cutting prices below purchase cost, prolonging downturns. In labor negotiations, incumbent workers value benefits like flexible schedules more than outsiders, complicating reform. Environmental policy faces similar obstacles when property rights are reallocated: fishermen compensated for quota reductions ask for more than new entrants would pay.

Negotiators counteract the endowment effect by reframing. Instead of "giving up" parking spots, city planners highlight the gains from safer streets. In auctions, structuring payments as staged gains rather than losses can temper attachment.